Elliptic Curves v2.0

(Dylan here) In January, Zhao Yu wrote a piece about elliptic curves. To prioritise the various remarkable consequences that follow from the theory, many things were black-boxed. Today, I would like to open the box. I expect to make a mess and not clean it up; I hope you are okay with that!

But first, some personal tales.

Qn. Is (olympiad) maths actually useful?

I've wrestled with this question for a long long time; it would be comforting to know that what I'm passionate about and invest a lot of time and effort into is also objectively meaningful. While I don't yet have a complete answer, here are my thoughts thus far.

First, I acknowledge the open-endedness and vagueness of the question as posed. What is (or isn't) mathematics? Does the answer vary between different types of mathematics (e.g. pure/applied, high school/undergraduate/research)? What does useful mean, and is there an objective aspect?

Of course, fuzzy terms and open interpretations doesn't stop us from asking such questions and trying to answer them anyway! For example, we intuitively work with dimensions and limits years before we formalise the notions in axiomatic rigour. We ask questions like "how fast does this algorithm run?" or "is this sequence chaotic and random, or rigid and structural?" with the same air of ambiguity. Yet we find ways to reasonably, rigorously answer them. Furthermore, we can accept multiple interpretations (e.g. an algorithm can have a vastly different worst-case runtime from average run-time) without contradiction.

Back to the question, we first list common positive answers. Maths is the language of the natural world, in the sense that seemingly magical physical phenomena may be explained by mathematical models. This is true both at the fundamental level (e.g. particle physics, gravity, electricity) and at the empirical level (e.g. weather forecasts, electronics, social diversity). Specific modern areas in which maths knowledge is highly valued are market predictions (finance), machine learning (computing), and precision design (engineering). Indirectly, maths encourages pattern recognition and abstraction, rational and critical thinking, and meticulousness, valuable qualities for many technical positions. There is also a strong association of mathematics with general intelligence (the ability to learn, absorb, and process information). And the patterns and structures in maths are innately beautiful, as they exist largely independently of our personal experiences.

Now for common negative answers. Maths neglects the emotional, social, and cultural aspects of a well-rounded education. There is low emphasis on understanding irrational behaviour (which is a big part of being human, thus more useful to study). Applications are concretely more impactful (e.g. saving lives, building houses, protecting the environment) and should drive theory (instead of studying maths independent of downstream applications). Maths wrongly encourages the idea that there is only one right answer, and that there are fixed methods to finding answers. Intelligence is not the most crucial ingredient of a meaningful life.

Now let's specialise the question to: is olympiad maths useful for high school students? Well, it depends. In the period of exposure to various aspects of the world and growing in maturity, maths is certainly important for reasons described above. But also other subjects are just as important, with ideas not captured by maths, as described above. Specifically (and in my personal opinion), the value of olympiad mathematics is the exposure to so many new ideas, examples, and concepts that we wouldn't otherwise encounter in real life. Think of someone who can perceive infrared in addition to the visible spectrum; the maths-educated similarly have added perspective.

But then what is the difference between mathematics and other areas of study (e.g. medicine, psychology), which also forge new lenses through which one perceives the world? I would say the key difference is that mathematics also develops the meta. By which I mean thinking about thinking, or thinking about thinking about thinking, or so on. Like simple vs. compound interest, but in multiple layers (like in idle games). Critically, the human intuition we have naturally, accumulatedly built up since we were babies only lie in the "first meta-level"; to go beyond human intuition and grow higher meta-levels (e.g. learning about how we learn), we have to learn to be comfortable with the abstract and foreign (e.g. "what if I lived in 7 dimensions?").

In short, maths makes one a better thinker in the meta sense, such as by introducing more ways to think (e.g. "this is water") and more questions to ask ("what is water?"). This is a slice of my current (vague and incomplete) answer; it hinges on many unstated assumptions and interpretations (many of which I probably am not even consciously aware of), so I expect disagreement (and I'd be interested to hear your thoughts too). Hope it was insightful anyway, and got you thinking about whether/how mathematics is useful to you.

Time for maths!

Elliptic Curves v2.0

This is not an olympiad maths post, but an exposure post. I will try to prioritise motivation of ideas at some intermediate level of accessibility (don't worry if you feel absolutely lost in the abstraction; you can always come back to this again). I will ask questions in square brackets [why?] which I feel are worth asking (and if you have the time, pausing to think about); some of them will eventually be answered, but I truly believe the questions are more important than the answers.

0. Spoilers

Zhao Yu's article is linked here; I would like to summarise some key elements. But this is also akin to a spoiler; in some sense, the answer is told to you before the question. So here's a spoiler warning; you may wish to skip this subsection and return to it after. But if you don't want to think so much, just read on (no guilt required).

Okay, summary time.

- An elliptic curve has both algebraic structure (given by a polynomial equation; notion of degree) and analytic structure (a geometric torus/quotient of the complex plane; notion of dimension). In addition, it has an abelian group law (i.e. a "zero" point, and a way to add/subtract points). [Do we already know of other such spaces?]

- The group law is a way to generate new points on the curve from existing ones. The fact that the group operation is given by rational-coefficient polynomials also means that rational points on the elliptic curve are stable under the group law (i.e. adding two rational points gives a rational point). This gives a solution to the fruit meme: begin with a small rational solution (but involves negatives, so not allowed), then keep adding it to itself until it becomes a positive solution.

- Elliptic curves have a relationship with elliptic integrals (i.e. integrals that you might get if you try to compute the perimeter of an ellipse). This perspective is no longer necessary in the modern treatment of elliptic curves, but it was important in the historical development of the theory. I will also not say more (since it does require some confidence in calculus to engage with).

- Elliptic curves have connections with number theory. Allow me to draw an analogy to the Riemann zeta function $\zeta(s) = \sum_{n\in \mathbb N} n^{-s}$, a special function over the complex plane, which has both analytic (i.e. calculus-able) and number-theoretic (i.e. factorisable-by-primes) properties. Similarly, the $j$-function is a special function over the upper-half complex plane, satisfying a specific set of symmetries, which grants it both analytic and number-theoretic properties as well. It turns out that perhaps the natural domain of the $j$-function shouldn't be "the upper-half complex plane", but "elliptic curves"; the set of elliptic curves (a very very abstract set) is naturally identifiable with (a quotient of) the upper-half complex plane. Everything in this paragraph is highly abstract and should just be ignored.

1. Background

1.1. Algebra

- We first encounter algebra in school as a tool to extract mathematics from a paragraph of information. For instance, the system $a+b=30, 2a+4b = 100$. [Can you think of a word problem corresponding to this system?] [Why is there only one solution?

- We also encounter non-linear equations such as $x^2+x=12$, perhaps related to "a rectangle of area $12$ whose side lengths differ by $1$". [Can you see the distributivity law encoded here?] [Why do we reject the negative solution $x=-4$? Do `unphysical' solutions still have use in, say, intermediate steps?]

- Other (Diophantine) equations such as $2x+3y=1$, $a^2+b^2=c^2$, and $w^4=z^4-1$. They may be solved over the integers: $(x,y) = (-1+3t,1-2t)$ (Bezout's and CRT), $(a,b,c) = k(m^2-n^2,2mn,m^2+n^2)$ (Pythagorean triples), and $(w,z) = (0,\pm 1)$. But they could also be solved over the rationals, reals, complex numbers, integers modulo $5$, rational-coefficient polynomials, real power series, etc. [What are properties of a general space $R$ for which such polynomial equations make sense, and can be solved over?]

- Algebraic identities, such as the $2$-square identity $(a^2+b^2)(c^2+d^2)=(ac-bd)^2+(ad+bc)^2$ and Sophie Germain's identity $a^4+4b^4 = (a^2+2ab+2b^2)(a^2-2ab+2b^2)$. [What are properties of a general space $R$ for which such identities hold true?]

- Symmetries of polygons and polyhedra; the Gaussian integers $\mathbb Z[i]$, or the space $\mathbb Z[\varphi]$ in which Fibonacci numbers "naturally live" (see my previous post); lattices in the plane (discussions for another day).

1.2. Geometry

- Euclidean (planar/2d) geometry: lines, circles, ruler-compass constructions. [Why can't we construct $\sqrt[3] 2$ or $20^\circ$ using a straightedge and compass? Is there a conflict between the continuous/analytic nature of the real line, and the discreteness/rigidity of ruler-compass constructions?]

- Some remarkable results: (a) Pappus' theorem "$2$ lines, $3$ points on each line, draw the $3$ crosses, the $3$ intersections are collinear". It's amazing that such a non-trivial result arises from straight lines alone (no compass needed!). (b) Pascal's theorem "$6$ points on a circle, draw the $3$ crosses, the $3$ intersections are collinear". [Why do their statements look so similar? What does two lines have to do with a circle?]

- Geometric transformations: rotation, dilation, reflection, inversion, (skewed) scaling, shear, projection.

- 3d geometry: that the surface area of a sphere and its bounding cylinder are equal, but volumes are in the ratio $2:3$; or a result/observation by Eudoxus that "the intersection of a sphere with a cylinder tangent to the sphere, is a figure-eight loop traced out by a composition of two rotations". [Can you prove it?] This result falls in the meta-picture of "problem = constraints, solution = parameterisation"; one may wish to draw a meta-link with the problem-solution pairs listed in point 3 of algebra.

- (Cartesian) coordinates: now every theorem in geometry has an algebraic proof! [Does that mean geometric results have algebraic meaning?] Also, objects now have a notion of degree (e.g. a line/plane has degree $1$, a circle/ellipse degree $2$, based on the associated polynomial) and dimension (intuitively, the number of coordinates required to parameterise the object).

- Projective geometry: imagine a painting of train tracks; the tracks are parallel in real life, but meet at a point on the horizon on the picture. One may understand the projective plane as gluing on a "line at infinity" (or if you prefer, a "circle of infinite radius" at infinity) at which parallel lines meet. One may also opt for the view that the projective plane is the set of lines in 3d through the origin: if you think of the plane (the ground on which the train tracks lie) as $z=-1$, and place the painter/eye/observer at the origin, each point on the plane then corresponds to a unique "line-of-sight" through the origin, but there are also lines through the origin parallel to the plane (corresponding to the horizon line, i.e. line at infinity).

- Alternative coordinates; embedded geometry (e.g. knot theory); spherical/hyperbolic geometry; general surfaces, manifolds, bundles (discussions for another day).

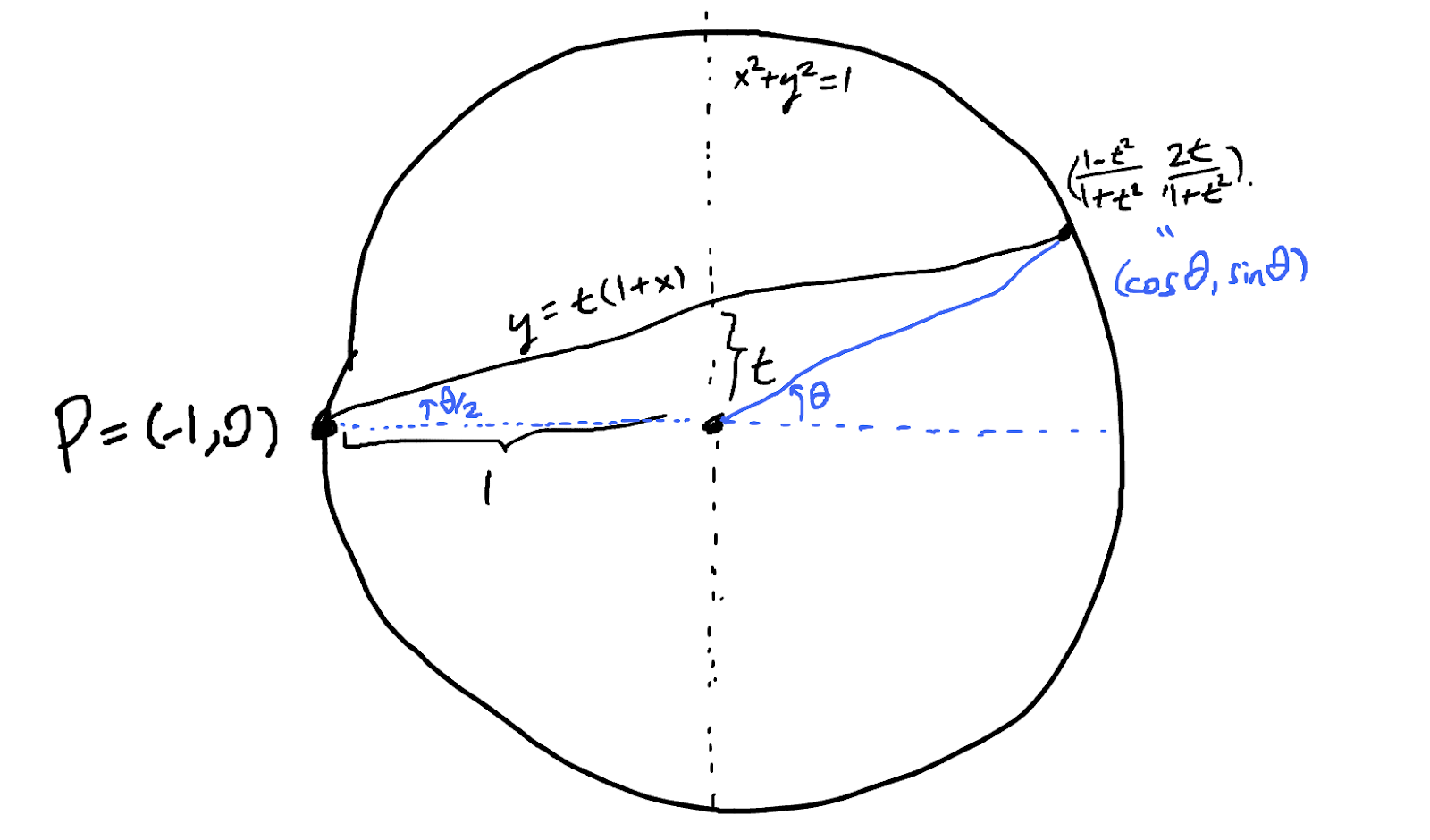

2. The unit circle

- Draw the line $PQ$.

- Draw the line through $O$ parallel to $PQ$.

- This line intersects the circle at a second point $P\oplus Q$.

- Draw the line $PQ$; it intersects the line at infinity at some point $R$.

- Draw the line $OR$; it intersects the circle at a second point $P\oplus Q$.

3. What does all this have to do with elliptic curves?

Earlier, I asked about why Pappus' and Pascal's theorem are so similar in configuration; in particular, what does two lines have to do with a circle. The answer is that they are both conics (i.e. cut out by degree-$2$ polynomials)! [Why can two lines be cut out by a degree-$2$ polynomial?] The optimist would then try to see if Pascal's theorem generalises to $6$ points on any conic (i.e. degree-$2$ plane curve, e.g. ellipse/parabola/hyperbola). The answer is yes! [Can you already see it to be true for an ellipse? Think of what transformations you can do to the plane!]

Well, actually the $3$ lines in Pappus' theorem (the $2$ initial lines, plus the final line of collinearity) are rather symmetric in nature. So perhaps the right question was: what does three lines have to do with a line and a circle? The answer: they are both cubics (i.e. cut out by degree-$3$ polynomials)!

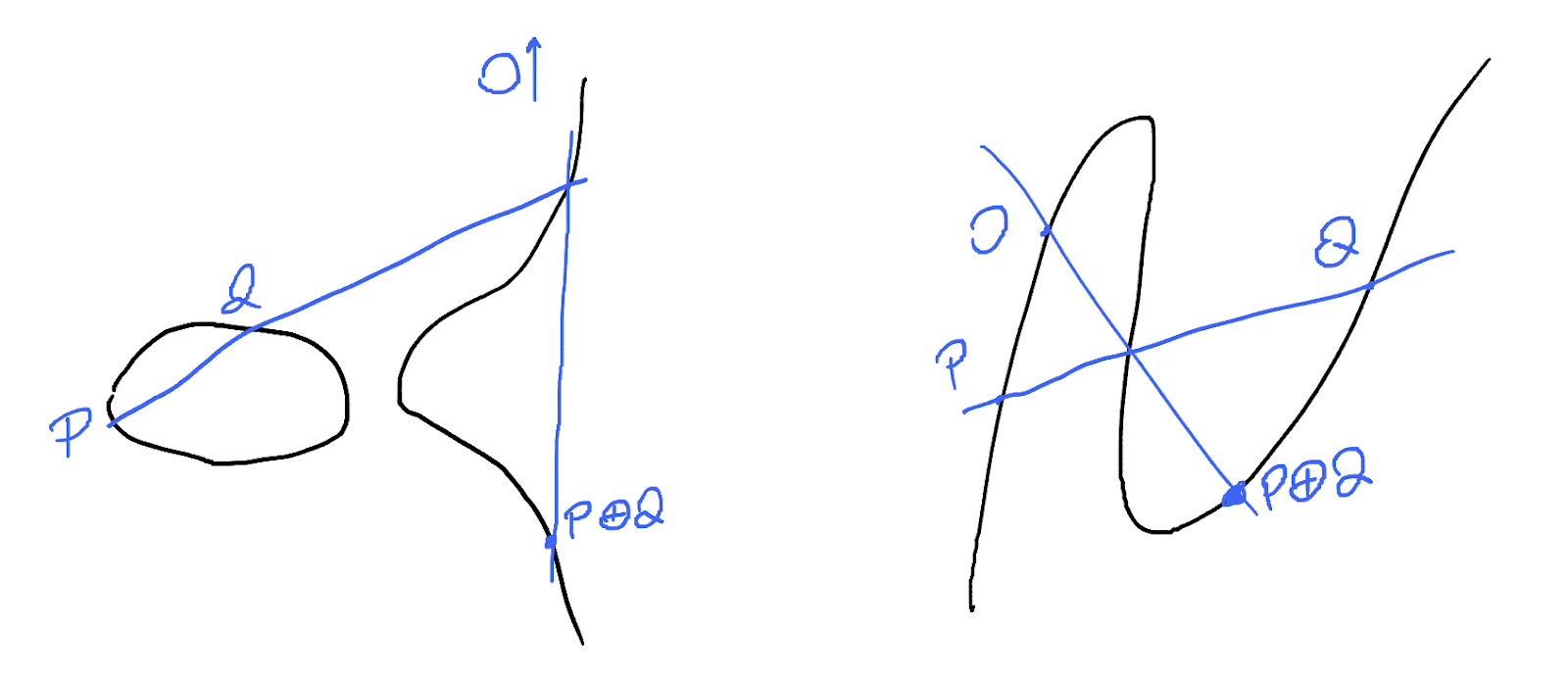

Now that we know the group law on the unit circle, let's try to generalise it to define a group law on a general cubic:

- Fix a "zero" point $O$ on the cubic.

- Given two points $P,Q$, draw the line $PQ$; it intersects the cubic at a third point $R$.

- Draw the line $OR$; it intersects the cubic at a third point $P\oplus Q$.

4. Conclusion

On a complete tangent, writing this blog post reminded me that back in the days, Zhao Yu and I participated in the PuMaC '15 Power Round, which was about elliptic curves. I have long forgotten my experience of it back then, but I'm sure it had some unconscious effect on us. The PuMaC Power Round is one (of several) entrypoints into engaging with undergraduate mathematics at the high school level. For convenience, here are the past year Power Round topics (listing in case any of it interests you): algebraic geometry (’23), PID structure theorem (’22), mixed volumes and convex bodies (’21), billiards and ant-paths (’20), extremal graph theory (’19), combinatorial game theory (’18), Lie algebras (’17), pseudorandomness and cryptography (’16), elliptic curves (’15), four-square theorem (’14), knot theory (’13), algebraic numbers and diophantine approximation (’12), projective and perspective geometry (’11), graph minors and four-colour theorem (’10), lattice theory (’09), quadratic forms (’08), lattices (’07).

Happy mathing!

Comments

Post a Comment